Play some Perunazca – Dawn in the Andes – Pan Flute music

while you read. Just hit the play button on the left.

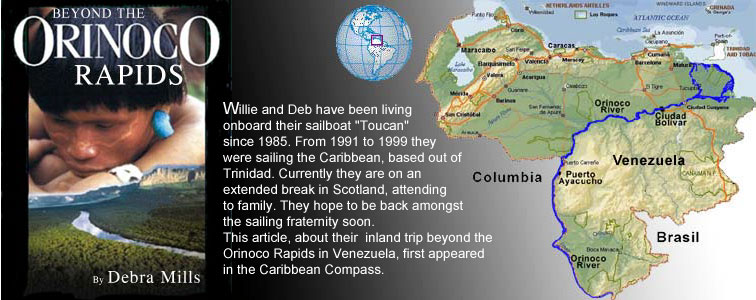

Once you’ve settled into the cruisers’ lifestyle at Puerto La Cruz, it is worth taking the time to explore beyond the harbour! Here’s our story about our trip into a remote corner of Venezuela.

It started when Kaye pointed to a dot on the map midway down the Columbian – Venezuelan border, and exclaimed, “This is the only part of Venezuela that we haven’t visited yet – let’s go!”

After a few days of pouring over the Lonely Planet Guide to Venezuela, Bill and Kaye from “Free Spirit” and Willie and I from “Toucan” hopped on a bus for the 18-hour trip from Puerto La Cruz to the frontier town of Puerto Ayacucho, Estado Amazonas.

We didn’t make any prior arrangements with tour guides or agents, but as it turned out, it isn’t absolutely necessary. During our first breakfast in Puerto Ayacucho, we were approached by no less than three tour agents!

Deb & Kaye changing buses in Ciudad Bolivar

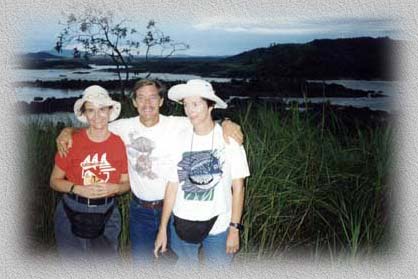

Deb, Bill & Kaye at the summit, Orinoco Rapids at Atures

After breakfast we chose Autana Aventura Tours, which gave us a great deal on a three-day river trip onboard a bongo (dug out canoe). Since most trips are booked months in advance by overseas tourists, the tour operators often find themselves with empty places and are willing to give a discount.

Mercado Indigena – Puerto Ayacucho

We filled the next couple of days by exploring the town. Again and again, we went back to the Mercado Indigena, an open air market that is famous for its exquisite baskets and Indian artisan crafts. Across the street, the Museo Etnologico provides further insight into a variety of Amerindian cultures.

Autana Aventura Tours took us on a day trip to the natural rock bed waterslide at the Parque Tobogan de la Selva, just a few miles away. The ride is a bathing-suit-bottom-destroying ride akin to white water rafting without the raft. The day was topped off by an easy climb to the summit of Cerro Zamoro. The reward is a glorious sunset on the horizon and below, a spectacular view of the Atures Rapids, which effectively block further navigation of the Rio Orinoco.

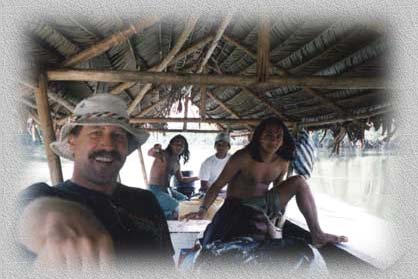

On the morning of the tour, we were driven south past the rapids to Puerto Samariapo. This is where the road ends and the jungle begins. Along the banks of the river, sixty-foot-long cargo and passenger bongos, bows dug into the muddy bank, busily load up families and building materials. With our fellow adventurers from England and Germany and our guides Macuto and Macare, we boarded our canoe. Propelled by a 40-hp Yamaha outboard, we headed off into Piaroa Indian territory.

Our 60 foot Bongo – skimming along the Rio Orinoco

After a few hours, all signs of western civilization ceased. Thin brown children waved to us from shore as we cruised by the traditional villages. At the bends in the winding river, we often saw fishermen. Singly or in pairs, they cast line, hook, or loose-weave baskets from their low-freeboard bongos.

Our helmsman slowed down for scenic views of the distant Tepui Autana (‘table mountain’) and to run minor rapids. Turning east, we passed over the distinct line in the water which marks where the brown Rio Orinoco meets the inky black Rio Cuao.

That afternoon we arrived at a ‘model’ village called A diHua’a – “IcHa Toro. The population of 200 boasts their own scaled-down hydro-electric generating station and the accompanying street lights. The locals were eager for fresh competition on their volleyball court and we took up the challenge. No one kept score, but we conceded defeat when it was time to set up our camp before nightfall.

Our camp was across the river and up stream from the hydro plant. All the power lines lead to the village, so we made do with candles and flashlights. In the fading light the porters hung our hammocks and cooked a tasty chicken and rice dinner in a huge cast iron pot over an open fire.

After dinner, we played a dice game called “Pigs”. While the Gringo heathens concentrated on technique, our head guide, Macuto, prayed to the Piaroa gods for “el suerte” (luck). He tossed and won by a landslide!

With evening ablutions came the discovery of the sanitary facilities and a test of nerves! It is a simple walled outhouse, surrounding a modest hole in a concrete floor, but no one lingered long in there because of the permanent residents. We were fearful not of the mosquitoes waiting for fresh meat, not of the camouflaged wet-cement-colored frogs gently croaking, but of the mysterious winged-beast whose lair was deep within the dark abyss of the ‘toilet’.

Macare with supper

Indigenous artwork at the museum

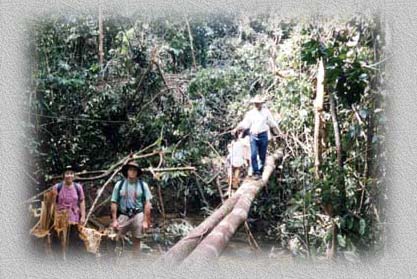

Bill traversing a log bridge

At 6 am the next morning, I sat on the edge of the cliff overlooking the river and in the serene quiet, watched the mist burn off the faraway tepui. Breakfast was cowboy coffee, fried Indian bread, ham and eggs washed down with ‘river’ Tang. Although a little anxious about drinking river water, no one had any ill-effects. We boarded a smaller bongo upstream of the rapids and power plant and continued along the Rio Cuao. About forty minutes later, the driver pulled a sharp right, grounding the bow on a mud embankment. From there we hiked for two hours along an ancient Indian trail to the next camp.

Kaye drinking fresh water from a tree vine

The dense canopy of the rainforest protected us from the full force of a tropical downpour. Spirits not dampened, we marveled at the flower blossoms punctuating the greenery that surrounded us. At our feet were colorful red, yellow, and orange tree roots. The terrain was challenging as we negotiated the caved-in burrows, fallen trees and muddy pools that obstruct the trail. At a height of 10 feet, we crossed larger streams over mossy bridges. The most interesting one was simply a single 30-foot log. Now and then, the sun shone through the foliage, revealing the majesty of outlying tepui.

Along the way Macuto caught a 2-inch-long yellow-striped black frog and demonstrated how Indian hunters use its secretions to poison their blow darts. He also hacked off a water laden liana branch with his machete and gave us a woody-flavored drink. Macuto then fished a tarantula spider out of its den using a slender rod. To show us the fangs on its underside, he deftly manoeuvred each leg over top its plump body. The sight of the furry brown four-inch-long creature quickly exposed the two arachnaphobics amongst us.

The trail opened up into a clearing with two thatched roof shelters. Close by, we could hear sounds of rushing water from a natural waterslide emptying into a pool. After a slide and a swim, some of us went exploring further along the trail with two guides. They led us straight uphill to the top of vertical rapids. As we stood watching, they traversed the falls by leaping from one submerged slimy rock to another in the fast flowing waters. We told the bewildered guides that we would prefer, no – we needed, a different route!

Hello mother, hello father, here we are at camp…….

After dinner we hit the trail again. In the pitch darkness and eerie stillness of the jungle, the trees, leaves and dead logs glittered with tiny specks of light. This dazzling “sendero luminoso” (shining path) is illuminated by phosphorescent fungus. Later, by candle light, Macuto told us, in Spanglish and through charades, the elaborate tale that is the basis for the Piaroa religion. In the beginning, the Autana Tepui was the stump of a gigantic tree, which seeded the area with all types of fruit trees. The twisting tale of men, animals, and greed ends with the Piaroa being allowed to stay in this place if they used the fruits wisely and fairly.

Deb handing out lollipops

On the way back to civilization, we made several inland side trips. We toured a seasonal manioc manufacturing settlement where nearby villagers come to harvest, process and bake the flat bread with traditional tools and methods. At anther village, Kaye traded for an authentic ten-foot-long blowgun. Everywhere, the curious children were delighted with the lollipops we gave them.

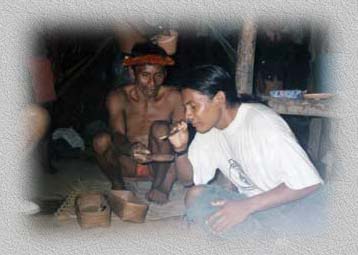

The highlight of the return trip was witnessing and participating in an ancient religious ritual. In the shadowy darkness of a Shaman’s hut, the wizened old medicine man sat cross legged on a low wooden stool. With a mischievous smile, he gestured to us to sit on the mats encircling him.

Macuto participates in the Yoppo Ceremony

Wearing only a bright red feather headband and matching loincloth, he arranged his paraphernalia in front of him on a woven mat. He took a black lump of the crushed seed and plant mixture and placed it on a flat wooden mortar. After pulverizing it with a pestle, he manoeuvred it around using a long black curassow feather and a round porcupine quill brush.

“Yoppo Man”

Although other tribes swear that the practice causes brain damage, Macuto assured us it was “all natural, very good.” Truly awed, we watched in respectful silence.

With due reverence, the devout followers took their places beside the Shaman. Through a six-inch double-barreled bone nose pipe, each man snorted the pile offered to him.

So far there are parallels in the western world, but strangely, the custom here is to comb your hair in order to fulfill the ultimate goal of seeing the spirits. However, despite vigorous grooming, our delegate got only a “good buzz” and the nickname “Yoppo Man”. Our guides also partook so on the return trip Bill decided to try his hand at bongo driving and steered us home.

HOW TO GET THERE: Bus – Puerto La Cruz to Cuidad Bolivar to Puerto Ayacucho (17$US, 16-18 hours) plus taxis to/from station (5$US). Air – Barcelona to Caracas to Puerto Ayacucho (110$US) plus taxis to/from airport (12$US)

ACCOMMODATION: 5$US to 20$US per person per night

MEALS: 10$US per person per day

TOURS: Approximately 50$US per person per day all inclusive Autana Aventura, Avenida Amazonas Tel: 048-210-141 Fax: 048-212-619

GUIDE BOOK: Lonely Planet guide to Venezuela (Available at Xanadu Marine, Puerto La Cruz)

WHAT TO BRING SUGGESTIONS: Baygon bug spray for hotel cucarachas. Ear plugs for buses with sound systems. Warm cloths for buses with air conditioning and sleeping outdoors. Garbage bags to cover knapsacks in bus cargo holds and bongo. Water purification tablets. Aralen tablets to be taken one week before trip to protect against malaria. Money belt or secure pocket for money and passport. Insect repellent. Flashlight. Light rain gear. Candy or other small treat/gift for every child in the village.

1,796