We were now living in Scotland looking after my mum who had Alzheimers and Toucan was still in the Caribbean. We decided to bring the boat over to Scotland, but Deb had to stay behind to look after mum, and that meant I would have to single-hand sail the boat across the Atlantic.

This was in 2004 and the boat had been sitting on the hard at Trinidad and Tobago Yachting Association (TTYA) for 4 years now. When I arrived nothing on the boat worked including the engine – despite having the engine fogged before we left in 1999. So I started the job of going over every system and repairing or replacing them. As well as adding a few extras like the new radar unit and a 2nd hand (really efficient) high tech design wind generator, that I swapped for the old canvas boat cover we installed before leaving. The injectors were totally clogged up and the high pressure pump was jammed, so the engine had to be taken apart and the parts taken over to the local repair shop, who serviced them. All the belts filters and pump impellers had to be changed. Even the engine contoller in the cockpit had to be totally serviced as it was all seized up. And it turned out that the old trusty Auto pilot “Otto” it’s gears were all worn from many years at sea. None of the navigation lights worked neither did the propane solenoid used for cooking.

The person I had left the keys with and arranged to keep an eye on the boat, did a great job on the canvas cover, but had left a fan on in the V-Berth, so the 3 large battery banks were completely dead and needed replacing. The radio that was mounted in the navigation station was missing, and so was the tiller. The most difficult to explain was the “Very” pistol – a WWII flare pistol, that was on the entry manifest that was with the customs office and had to be shown upon leaving the island (oops!). Even the portable (engine) 12 volt service lamp had been plugged into the 110 volt mains and obviously no longer functioned. There was an entire can of blue boat paint that had been spilled right across the cockpit seating and floor and it looked like someone had tried to remove it using a chisel – I did not have any blue boat paint on the entire boat – mystery? There was an ant trail to a bag of sugar that was left in the galley, and there was a nest of hornets firmly attached to the bottom of the boat. Toucan looked in sad shape indeed.

I got to work starting with the mast that was on saw horses on the ground besides the boat, and worked from first light to dusk every day, and the heat and the mosquitoes were overwhelming. Once all the work had been done to the outside of the boat, and the bottom was freshly painted, and the topsides were all polished and waxed, and the mast had it’s new radar installed, and all the running lines installed, and all the navigation lights, and the wind instruments and the radio antennas installed, and having replaced the old cables with new, and checked that everything now worked. I launched the boat raised the mast and had her towed to a mooring well away from the mosquitoes and the constant yard dust.

Now all the inside jobs had to be tackled. The engine was stripped down and the high pressure pump was removed and serviced, the injectors were replaced with a set that we had carried on the boat since leaving Canada. All the belts, impellers, oil and filters and coolant hoses were replaced. Serviced the engine cockpit controller. I reinstalled the solar panels that were taken down for the long storage period. I replaced the wiring for the propane solenoid, and the radio equipment. I installed the high tech wind generator on a new mount as well as breaker and amp meter dial control panel for it. I installed the radar display so that I could see it from the cockpit while underway as well as from the navigation station. I installed a drink and binocular / hand-held radio / emergency horn box in the cockpit. Replaced the fish-finder / depth sounder membrane buttons with radio shack momentary push buttons as the membrane buttons had stiffened and no longer worked. I reinstalled the ham radio sloping antenna. Rebuilt the raised toilet floor as the original one had rotted away, and installed a new head (toilet). Serviced all the fresh water pumps for the galley and the head. Replaced all the rigging wire for the mast, and the lifelines that ran around the boat. Installed a new fluorescent salon light and the red navigation (for running at night) light, as the old ones had given up the ghost. Installed a new tape recorder at the navigation station to tape any conversations about the weather. I replaced the 3 huge truck batteries with 6 – 6 volt Trojan Deep Cycle batteries 2 each in of the 3 banks ready for the alternator, solar panels and wind generator to charge. I had Jeff’s assistant come on board to service our small refrigerator, as the CFCs must have all leaked out, and after a quick recharge it seemed to work as good as new. I also had the dodger clear “glass” replaced and the Sunbrella restitched. I was lucky to get a SCS microprocessor Pactor modem that a fellow sailor had no use for – all for just adjusting his ham radio to tune in the BBC – as that was all he wanted it for. This allowed me to have email on-board for the voyage, cannot tell you how important that turned out to be.

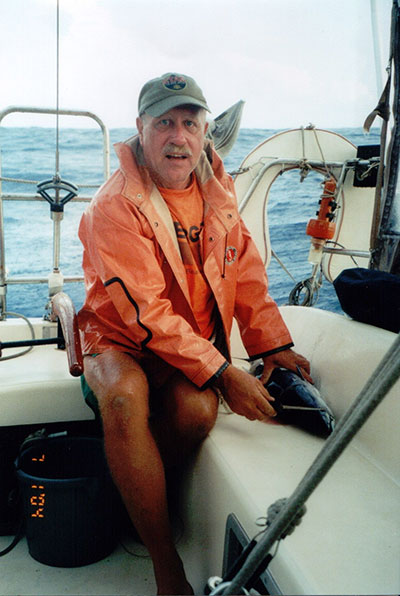

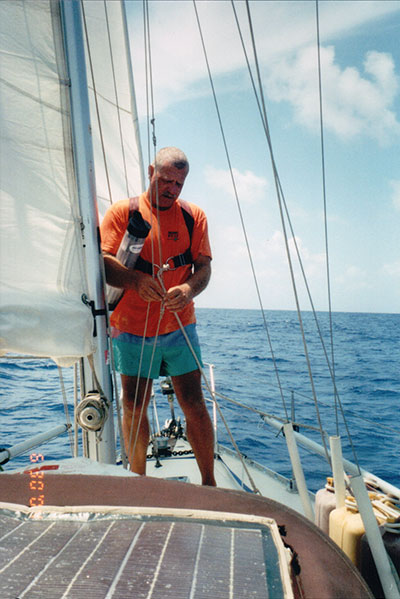

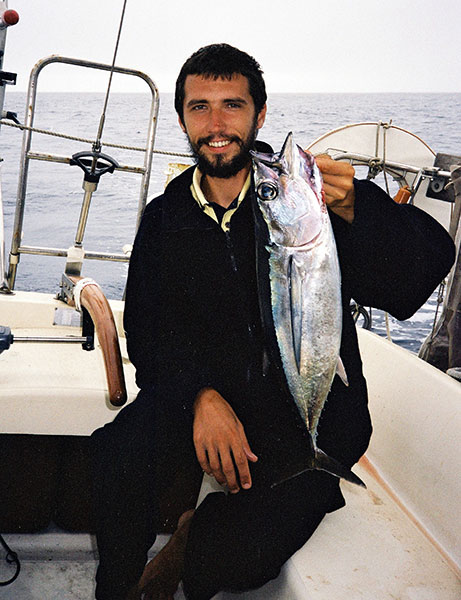

Preparing a freshly caught fish while underway onboard Toucan.

I also secured a 6 man life-raft (thanks Jasmine!), and installed it securely on the deck immediately in front of the dodger. This was the full kit, which was far better than having our small inflatable Avon dingy secured upside down on the foredeck. Which to say the least even although it was well lashed down, it still was a bit dangerous in in any storm conditions. the funny thing about the instructions printed on the outside of the valise, instructed you to throw the life raft overboard, and had the instructions in picture form (with a small painter – line still attached) in order for it to automatically inflate. It took 2 of us to lift it into position in the first place, and even that was a struggle! There would be no throwing of a 6 man life raft that was for sure. If the boat was sinking it would be much easier to cut the restraining straps and roll it off, or better still, let it float off.

In addition to all the survival kit in the life raft (I was not sure what it contained), I also prepared a very extensive abandon ship bag, which was stored below next to the companion stairs. Which is ready to go at a moments notice. This kit contained all the items that I would need if the worst happened and I found myself in the life raft in the middle of nowhere. This fairly large bag contained an EPIRB (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon), spare food, water, all the flares and a flare gun, fishing line and lures, foil blankets (great for water collection) and a dingy repair kit with Hypalon 2 part epoxy glue that I had made up myself from years of repairing fellow sailors dingies, Ziplock bags (great for storing fresh water), a filleting knife (with holster) and a sailors knife, and a stainless steel polished signal plate, a hand held “hocky puck” compass, a mini pair of binoculars, our old TTC whistles (from driving the subway train), a dingy pump, a waterproof torch with spare batteries, spare polypropylene line, and a survival at sea paperback book, all sitting in and on top of a bucket in a sail bag. All the items like the flares and food and batteries and paperback that needed to be waterproof, were all packed in the 1 gallon Ziplock bags. I planned to grab the hand held VHF radio and the GPS in the companion way and quickly throw them in the grab bag on the way out, as I did not have any spares of these items. I would have liked to have added a hand-held water maker, that converts salt water to fresh water by a hand operated pump which filters the saltwater through a membrane in a reverse osmosis process, where fresh water seeps out through the membrane from the high pressure area to the low pressure area, but there were too expensive and they required a lot of pumping for a little return in fresh water. I always fancied one of the blowup passive solar still condensation type powered by the sun. In which you put in some salt water and leave it in the sun and it heats up and evaporates the water in the form of moisture which condenses and collects on the inside of the upper ball and trickles down to be slowly collected via a tube for drinking. But in all the chandlers we visited over the years we never came across one of these kits. We had read all the books like Steve Callahan’s – Adrift, in which he spent an ordeal of 76 days floating across the Atlantic (the other way) to the Caribbean, and somehow managed to survive (just). Good reading before planning to make any long distance passage. The funny thing with all these books the majority of small sailboats that were sunk, seemed to be sunk by whales. I do not know if this was a collective revenge to sailors for all the whaling that was done over the last couple of hundred years, or it just sounded more dramatic that colliding into a semi submerged container that had fallen of one of the large container ships and been floating around the sea waiting for some poor unsuspecting sailor to come by. In any case, before leaving Canada we foamed and fiberglassed all the forward lockers below the waterline in case we were the unsuspecting sailors coming by. In the 3rd leg of this trip we were followed by a 60 foot Fin whale who kept coming back, and at one point went under the boat, and as Lucas was shouting “That is beautiful”, I was murmering “That is too close, that is way too F^%&*$g close”, I guess it all depends on your perspective. I digress.

I also strung up extra netting in the salon for all the extra food, and securely roped all 6 of the spare 6 gallon water containers below the salon table, and the 3 – 5 gallon diesel fuel containers in the tiller transom seat, along with 2 extra gasoline containers for the dingy engine that just happen to wedge all the spare fuel containers quite tightly in the transom. With enough provisions to last a month, it was finally time to slip the mooring at TTYA and head out of the Bocas of Trinidad to the Caribbean Sea to start the first leg of the trip North to Bermuda.

I met Matt a sailor based in Martha’s Vineyard, USA, when I was still on the hard at TTYA (during Carnival time), he was there to sail a boat back to the US for resale. The boat had quite a few problems and needed extensive repairs before being ready to take on a big trip. He had arranged for Jane, another sailor who belonged to the same Blue Water sailing club as he did, to fly down and sign on as crew and help sail the boat North to the American Virgins. Their members traveled to many destinations in pursuit of real blue water sailing experiences. Matt also asked me to join the boat as crew as I had extensive knowledge of all the islands where they intended to sail. Since I was in the process of getting my own boat ready I could only agree to join them for the overnight sail to Grenada and as far north as Carriacou. After that it was day sails – island hopping to their destination. Which was straight forward enough. The boat had intermittent engine problems and Matt was glad of the extra crew to lend a hand. I do not know how many times I had to quickly jump down and bleed the fuel lines and get the engine re-started while we were negotiating an entrance to a bay with reefs all around, or a dock. Matt had agreed to fly me back to Trinidad whenever I left the boat. But when we arrived in Carriacou I saw another sailing friend anchored in Tyrell Bay, George, on the s/v The Vagrant. A single hander who based out of Carriacou, whom Deb an i had met quite a few years ago in Venezuela, and had shared a few Carnivals in Trinidad with. George just happened to be sailing back to Trinidad for a change of scenery. I gave him a shout and asked if he would like some company on the South bound trip, which he gladly said yes. So I signed on and reported for duty early the next morning in spite of Matt and Jane having hidden my deck shoes in the cooler box, an an attempt to make me miss my passage, and have to stay onboard. Nice try, as I never would have dreamed anybody was crazy enough to put my well worn deck shoes anywhere near where food or drink would be kept! I said my farewells to my old crew, and would miss them as they were fun to sail with. And once I was aboard The Vagrant as crew, we pulled anchor and had a great sail back down island. Once back in Trinidad I was able to continue working on Toucan to get her ready for the trans-Atlantic passage.

Since I intended to do a straight run from Trinidad to Bermuda, and the sailing plan was going close to all the Caribbean islands which meant a lot of inter island ship traffic and that would mean that the radar alarm would be going off all the time. It would be better to have an extra crew member to split the watches with. I originally asked a good friend Rab in Scotland to join me the previous year for the entire voyage, but when it came time to fly in for the trip he was going through a lot of family issues and sadly could not make it. A once in a life time trip that he missed, and I have managed to remind him of it to this day. Perhaps he would have an entirely different opinion of the trip once he views the video at the end of this post. So I asked Jane from the Blue Water Sailing club in the States if she would like to join Toucan as crew, do the 1,500 mile blue water sail from Trinidad to Bermuda. Thankfully she agreed, and arranged to fly to Trinidad a few days later.

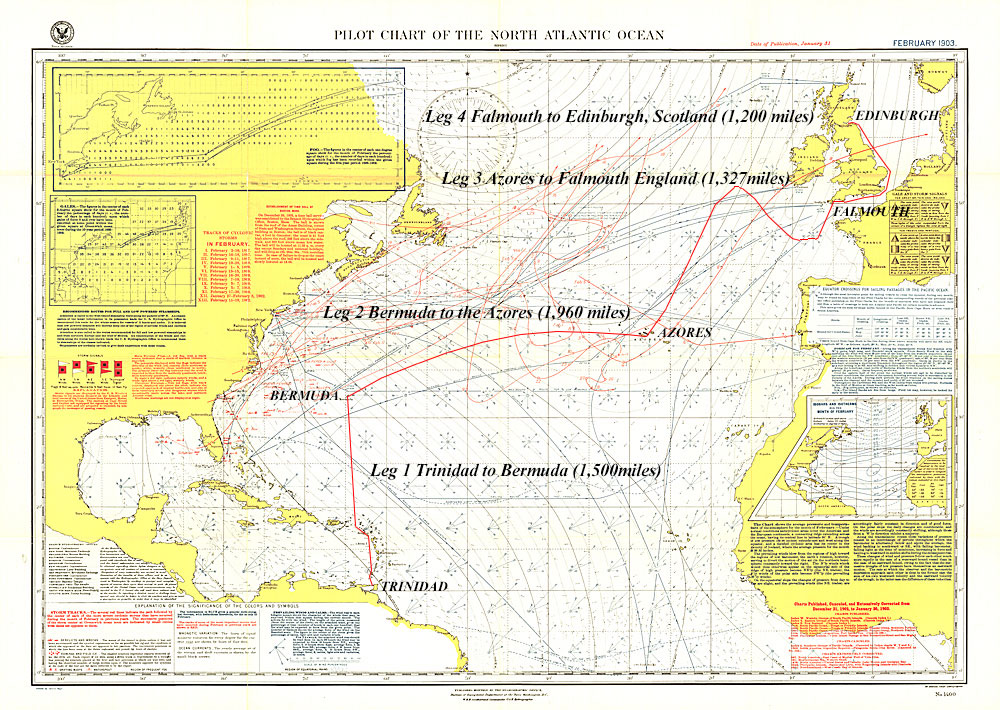

Leg1 Trinidad to Bermuda (1,500 miles)

Antigua

Arriving in English Harbour, Antigua.

By the time we had sailed overnight and reached Grenada and turned on the engine due to light winds in the lea of the island, and to help charge the batteries, I noticed that the engine was leaking oil from the emergency hand crank housing. A quick look at the service manual told me that there was a circular spring loaded seal there, that must have dried out over the 4 years, and it needed replacing. I cut a small donut shape from a sponge and secured it in place and this would contain it for a while, since we were not really using the engine other than 1 hour per day. Also the refrigeration packed it in again. So a stop off was in order, but where? As we already passed Grenada and did not want to go back, so I thought that we could stop in Antigua, as it is English speaking and had a history of yachts visiting and had a small boat service industry in English Harbor (if you can call it that). I tucked away in the rear of English Harbor, and had to order parts from Canada (1 week for delivery), so I thought I would have the rest of the dodgers spray curtains re-stitched, while I waited. The laptop (thanks Rab!) was intermittent and it turned out that it had a hairline crack in the circuit board where the power plug attached, and needed re-soldering. Fairly easy job. This was a vital piece of equipment. So I thought I had better take advantage of the break and go over every system while in a calm anchorage, cause “there ain’t no plumbers at sea!” A refrigeration guy came out to look at the fridge, with no attempt at recharging and after 5 minutes of a quick look, suggested I buy a new one. US$75 for that diagnosis, tell me something I didn’t already know. I thought he would spend at least 10 minutes giving it a gas charge and then see. The throw a way culture has reached the upper islands. I guess we spent too many years in Trinidad and we were too used to the way they still do things there, they would have had it out and found any micro leak and fixed it, re-charged it and re-installed it for fraction of the price. Oh well – no fridge on this voyage. The new circular spring loaded seal for the Yanmar diesel engine worked out a treat. I also climbed the mast and re caulked the wiring connection from the radar to the inside of the mast, as well putting a really good seal on everything I could find, and double securing everything on deck – 3 anchors, 2 whisker poles, life-raft and so on. The deck looked fairly striped now as the things that you would have on deck when sailing the Caribbean were now safely stored down below. As I expected that I would have to go through some very rough seas before journeys end.

Antigua to Bermuda

Rigging a new radar reflector while underway (note the harness)

So with everything checked and double checked, and a shaven head (to help conserve fresh water usage) we set off again for Bermuda. The trip was a bit rough going through the Leeward Islands, Monserrat, St. Kits and Nevis, St. Martin, and Anguilla, and there was fisherman’s pots to contend with as well as currents, and not surprisingly quite a bit of inter island shipping. Which meant that the watch had to be maintained round the clock. Alternating between us, 3 hours on and 3 hours off. This was rough on your sleeping patterns. Every 10 minutes a slow full sweep of the horizon, checking for any ships or boats, night and day. It was open ocean after the British Virgin islands, and a lot less traffic. Still the watch system had to be maintained The thought of sailing over the Puerto Rican Trench (some 28,000 Ft. over 5 miles deep) made me think, but you could not tell any difference on the surface. The depth sounder did nothing but flash “Error”, as it probably sent an echo and even at the speed of sound through water (3,315 mph) it would have taken 10 seconds to return and was probably too weak for the depth-sounder to pick it up.

During the 600 miles to Bermuda, we ran into a high pressure ridge that was predicted on the WeFax (Weather Faximilie – see article Here), and true to it’s form, the winds dropped to zero, and the seas went glass flat for 12 hours. So I lowered all the sails and lashed the tiller over to one side, and went for a swim in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. Weird being out there, and if you look in the direction away from the boat, scary!

A hard learned lesson from a similar (potentially dangerous) experience in the middle of Georgian Bay, The Great Lakes. A very hot day where there was absolutely no wind and I jumped in to get a drink that was knocked overboard – which had just happen to have landed the right way up and ice intact. It had a neoprene cooler jacket which acted as a float in the water. The main sail was just hanging there and the tiller was pointing forward. There was Deb and Heather and Terry on the deck, so I felt it was fine to jump in. As I retrieved the drink and as I swam around the back of the boat a small gust of wind came up and off went the boat. I said “Just start the engine and turn the boat around and come and get me – take your time – I’ve got a drink. But somebody maintain a watch on me at all times.” That boat got awfully small before it was turned around! So I imagine that I was a lot smaller in the water, and much harder to spot. Could have been a disaster. Lesson learned! This is the main reason for always waring a harness when on board when you are single handing or maintaining a watch system. The unexpected wave or miss-balance or a gust of wind from a different direction, and the boom swings over, and you go overboard – you are as good as dead. Because the sailboat will not stop. Some old salts will also trail a long heavy polypropylene line behind the sailing boat. So they can quickly swim around the stern of the boat to it, and at least try to pull themselves in a 5 knot current towards the back of the boat and try and climb back up. But I figured that if you are harnessed on at all times you will never go overboard in the first place.

The charging system was working great. The 2 rigid Siemens solar panels that were mounted on the rear arch were giving out a good 6.5 amps for the peak of the day, as apposed to the 2 flexible solar panels that were zipped into the top of the dodger and top arch covers, which only gave out a tiny trickle charge despite being the equivalent in surface area. The newly acquired high speed wind generator (swapped for a canvas cover) was in the region of 6 or 8 amps in 15 knots of wind and 25 amps in a 30 knot wind, and having it run 24 hours a day really helped. Far better than the 1.5 amp max wind generator that we installed in Canada. When ever we used the Ham radio to transmit for the ham nets or Herb or email we ran the engine to get the maximum voltage (14.2 volts) and we would let the manual alternator controller we built and installed in Canada run for about an hour each day, and it would add another 40 amphours to the battery bank running at 60 % the alternators rated value (55 amps). The original alternator that was on the engine lasted 12 years under these loads, and only then needed the bridge rectifier replaced, and is still happily putting out the amperage to this day. This put a small working load on the diesel engine and I’m sure this daily charging kept all the internal parts well oiled. We needed this much charging input as we ran the radar and the VHF radio 24 hours a day, which had a 4 amp and a 1 amp draw, and at night we had the running lights on, and the laptop got quite a bit of use, as well as the Ham radio while listening to the BBC. And there was the solenoid that drew 1 amp when ever we were cooking. So having no refrigeration with it’s constant 4 amp draw, actually helped.

Bermuda

Yet another squall before arriving at Bermuda

On the approach to Bermuda the seas had quite a swell, and there were several nasty squalls to go through. Jane did very well with her sailing experience and when it came time for her watches. She was constantly practicing her navigation skills using the charts and the small hand-held GPS we had on board, and was very pleasant to crew with. I know she would have preferred to stop in all the islands on route (so would I have), but we were already a month into Hurricane season. and I felt we really had to get a move on. She was very safety conscious and insisted we rig up jacklines for our harnesses, that run the entire length of the boat on both sides. And purchased a set which I installed and used for the whole voyage. Thanks Jane!

The entrance on the East side of the Island was well marked with buoys which were well out to sea. You had to contact Bermuda Harbour Radio to get permission to transit the entrance canal as there are large cruising ships coming in and out at all times and that left no room left at all in the canal for another vessel. But it was good to get in out of the swell. After tying up at the Customs dock, I had to walk back with the Customs officer to his office, and the strangest thing happened. I fell on him. I made my apologies and swore that I had not had a drink since leaving Trinidad – I never sailed and drank – ever. We continued to the Customs office and as we did so I fell on him again! I did not know what was wrong with me. In the Customs office I could hardly fill out the entry forms as the room was going round and round. The officer was having a good laugh and said he sees it all the time. After sailors have been to sea for a while once they step on land they often loose their balance. Yet on a bouncing boat a few minutes earlier – I was perfectly balanced – go figure!

We had to move the boat to a more out of the way dock, and there was several boats already tied up on the small dock, so as is the custom, I tied up to one of the boats that was already there. A Russian family with 2 adorable blond haired children. The boat in front was from Israel with a working crew. And there was 2 Polish racing style boats with 2 crews behind Toucan, which were tied up to on what looked like the wreck of an old dock. Just the skeleton was still there. As it turned out a Hurricane had been by the previous season and had damaged the dock and was still not repaired.

Toucan “docked” at St. Georges, Bermuda

So it looked like I was going to have to stay in Bermuda for a week while I ordered more parts. On the sail to Bermuda it turned out that the radar alarm was very low volume, and in order to change this I would have to purchase an Ratheon Radar Interface and connect it to a Radio Shack car horn – which I happened to have on board (in an earlier attempt to make a security alarm). This worked out too well in fact I had to stuff a small folded towel in the horn held in place with elastic band. But it still was enough to wake the dead! Perfect. There was a Ratheon dealer in the main town, Hamilton, and Ratheon also made an Auto pilot, which was lucky as the old “Otto” finally gave up the ghost and was steering the boat all over the place if we hit any rough seas. So with the parts on order, I set about making a few changes to the systems on board – endless fine tuning. While working on the boat doing minor repairs I noticed that the Polish boats must have had some problem with the solid rigging, as every day they had some poor sod hoisted in a bosun’s chair working aloft all day long. And I can tell you that even after a few minutes aloft, your legs go numb and it becomes quite painful. But to spend all day up there must have been brutal.

Waiting for the parts to arrive we rented a scooter from a back alley rental shop. The new shiny scooter rental shops located adjacent to the main docks where the large cruise ships dock and disgorge their passengers daily were really expensive to rent. But going several streets back we found a shop that would rent an older and not so pristine scooter for a week for the same price as the dockside rental shops did for 4 hours. This allowed me to re-provision and re-fuel the boat and pick up the parts from the main town – Hamilton at the other end of the island. It also gave Jane a chance to do a little touring of the island while I worked on the boat. Meanwhile Jane tried to get her son to fly in and and spend a week on holiday in Bermuda with her, but I think he was in the middle of an apartment move and could not make it, so after a few days Jane flew back to the States. Most of the small sailing boats had already left the island of Bermuda due to Hurricane Season being already a month old. And St. Georges bay was, according to the locals, quite empty. Most of the sailing fraternity had started sailing south for the Caribbean or other ports beyond by this time of year. So it made me want to get cracking on the trans-Atlantic trip as soon as possible.

Finally the parts arrived and I installed the radar interface, and installed and checked the new auto pilot – all was fine, and with the boat provisioned again, it was time to set off across the Atlantic for the Azores, a 1900 mile trip.

A skinhead pauses between boat jobs for a picture in Bermuda.

As I was busy filling the last of the water containers, and undoing the dock lines, a large group of tourists were walking along the dock, and saw me preparing to leave, and one of them asked where I was off to? I had to think for a moment and answered “The Azores” He had a puzzled look on his face, as he obviously did not know where they were. So I said “A couple of islands just off of Africa” The puzzled look turned to a complete surprise look and he said “What you are leaving to go there just now?” In my mind I had been gearing up to do this trip for many weeks and had been working endlessly on the systems and had some good sea trials on the way to Bermuda, all for just this moment of departure. And all I had left to do was untie the dock lines and give the front of the boat a little shove away from the dock, hop on and go. In his mind I was a little boat (compared to a their cruise ship) going for a sail around St. Georges bay. He called out in a large voice to all his friends “Hey, come and have a look, this guy is going to sail across the Atlantic by himself. He is one of those adventurer types, just like you see on TV”. To which all his friends came over and after a few words of confirmation, the large crowd waved me off the dock and wished me the best of luck! It was a nice send off, as I did not know anyone there. After a few minutes securing all the fenders high up in the rear of the arch while heading out to the entrance canal. They all were still there watching me sail off into the Atlantic. For some reason that made me feel really good.

One concern I had while leaving Bermuda was the rumors of piracy in the area. You are required to report by VHF Marine radio to the harbour control before transiting the entrance canal, and they ask you for the details of crew, destination, size of vessel and so on. I had heard that the criminal element (pirates) also listen into the marine frequencies for any easy pickings. And having to announce over the radio that I was single-handing on a small sailboat with a maximum speed of 6 knots, and would not be heard from for the next 20 days or so, would make me easy pickings for any armed and fast powerboat that fancied their chances. As there was practically nothing you can do if well armed pirates onboard a speedboat catches up with you and robs you once you have gone over the radio horizon. And the chances that they would shoot you and toss you overboard to remove any witnesses was high. This made me rather anxious for the first 24 hours, and I was on high alert with my “machete stopper” handy. I motor sailed due North and maintained maximum speed, instead of sailing the usual arc course to the Azores right out of Bermuda. After this period I would be more than 120 miles away from Bermuda and much harder to find on an unexpected course. Only then I could relax and get on with the business of sailing across the Atlantic.

Leg 2 Bermuda To the Azores (1,960 miles)

While underway I would wear my harness at all times, and clip on – even while in the cockpit. You never know if a rouge wave would come along and launch you into the sea. If I was harnessed on at all times, except when below, I would be guaranteed to never fall in. As I have said before the boat will not stop, and you are a goner if this should ever happen. For the next 6 days I only saw one other ship, as I was still out of the shipping lanes. So things were pretty quiet, as I got into a routine. I would call the Mississauga Maritime Mobile net on 14.121 Mhz every morning and check in with them with a position report. It was good to have someone keep an eye on you while you are out there all alone. I would continue to scan the horizon for any vessels, and tweak the sails to get the most out of them. Then have some lunch, which was pretty basic. And after that check every thing on board while picking up and processing several WeFax weather reports on the radio (see my previous article on receiving Wefax (Weather Faximile) Sailing the Caribbean – (Rough Guide) Here). In the late afternoon I would check in with Herb. A ham radio operator out of Mississauga, Herb Hilgenberg (Southbound II – VAX498), who would also keep track of your progress and give you a very accurate 3 day weather forecast for your immediate area. He was a very well known help to all sailors in the Caribbean and the Atlantic. Herb also knew where the Gulf Stream eddies were located and advise on any small course changes to take advantage of them. They would add a knot or two to your progress across the Atlantic, and that could mean an extra 20 to 40 nautical miles every day on top of what you were able to sail. Thanks Herb! You could also tell when you were in the Gulf Stream by the water temperature. It would be at least 5 degrees warmer than the surrounding sea. So I always had a little battery operated indoor/outdoor kitchen thermometer with the outdoor wire trailing in the water to let me know what the water temperature was. Then I would check the heading and check the boats’ position and fill out the ships log, and have some supper before it got dark. And boy did it get dark. One of the most amazing sights was when the sun had gone down, and before the moon rises, if the sky was clear, the stars would be out in full. The most amazing sight. Stars were thick, horizon to horizon. After my eyes had adjusted to the darkness, and I would just take some time and lie in the cockpit and stare up at the vibrant display, that you know must be there all the time but you rarely get a chance to see it. There was the Milky Way in all it’s full glory. Hard to find the words to describe it. I know it was possible to read by moonlight, especially near a full moon, once your eyes had adjusted. But I swear that you could read by starlight as well. Not as good as with the moon, but it was still possible, that is how thick the stars were. Another phenomenon was the wake of the boat. As the boat moved through the water it disturbs the little crustations and plankton and they glow chemically in the water. So your boat’s wake glows in the dark night. I’m sure the same happens in the daytime but it is too bright to see it.

Provisioning

The galley with a cooker, fridge (off) and a small sink, with fresh and salt water.

After week I ran out of fresh vegetables – lettuce and tomatoes, and bread, but had plenty of root veg such as potatoes, carrots, and onions, and celery and a cabbage. As well as plenty of eggs. Which I previously coated in Vaseline and repackaged to make them last longer. and plenty of oranges and apples and bananas and potato crisps and Tunnocks chocolate wafer biscuits, nuts and rasins. There was also a selection of dried sausage meats which were previously cured by hanging. And of course cans of almost everything I could find in Trinidad, and now Bermuda, stored in the lockers, including the sailors favorite – Bully Beef (corned beef). I still had plenty of a powdered flavored drink mix that I found in Trinidad, that was popular amongst sailors – Crystal Ice. It was sort of Cool-aid with artificial sweetener, so a very small pot of it went a very long way. This really helped the drinking of tank water go down, as in the tropics you tend to drink several large glasses every day. It surprised me how quickly you get used to not having refrigeration, and drinking luke warm drinks, as up until now I treasured a nice tall cold drink while in the tropics. And of course there was always plenty of coffee. I just did not have the patience or the time to do any baking on-board, like Deb would do when we were on our own, anchored in the little coral reef islands of Los Aves off the coast of Venezuela. So meals, all be it a little boring, was never the problem I thought it would be.

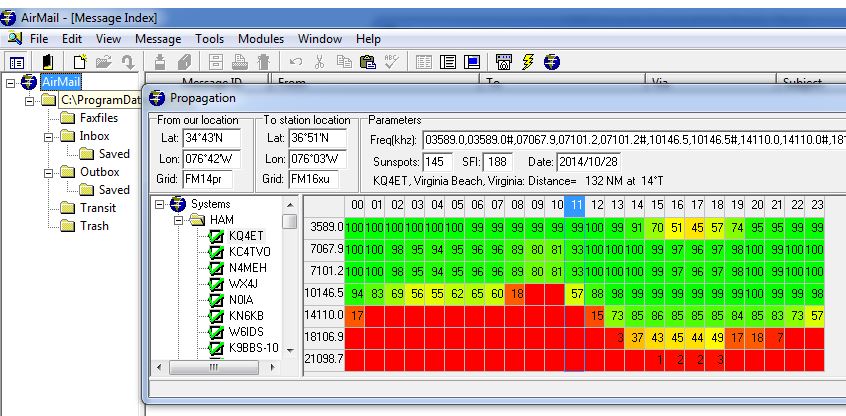

Airmail for Hams

Propagation prediction with AirMail for Hams software.

While in Antigua, I ran through a few practice email sessions, working all the frequencies, at different times of the day, and had everything down pat. If I needed to get a message out in a hurry, I wanted to be familiar with the process. The email software (Airmail For Hams and Pactor PCT-IIe v.3.7) in the laptop would control the SCS Pactor microprocessor (Modem) and in turn the Ham radio signal was sent out to a Ham operator in Florida, who would in turn receive the signal and convert it to packets that would be sent via the Internet to the final recipient as an email. The problem was you had to have this set up with the operator in Florida for at least a month, and establish that you were sending legitimate traffic before he allowed you a measly maximum connect time allotment of 20 min per day. Trying to get a radio signal through to Florida was very tricky even on the best of days. Compounded with this was the fact that you had to pick the best frequency and time and then with a meager 100 watt signal compete with the high power signals (1000 watts) of U.S. shore based Ham operators that were also using this service, or adjacent frequencies. Even when I finally connected and the 2 stations would swap traffic, I would frequently get blasted off the airwaves by the much closer Hams keeping their “hand in” even although they more than likely had a direct Internet connection! The receiving station would drop my weak signal and pick up the more powerful one. Some days I could not get through at all, no matter how hard I tried. I just had to be patient and wait for a gap in the signals. And when I finally connected, the email message was so slow – I could see the text being highlighted as it was being sent character by character, and most times having to repeat a single packet over and over again before moving on to the next character. The 20 minutes per day was never enough, so you had to make the emails short and precise in order to stand a chance to get them through. Battery draining stuff!

Radar

The new radar on-board Toucan

As single-hander this meant that if a sea watch was going to be made round the clock I would not get more than a half hours sleep at any given time. Not good for a 6,000 nautical mile sail. With the radar I could set a – ring guard – and any object entering this ring and producing a dot on the radar would set off an alarm and wake the crew – me. It worked out that 12 nm ring guard was the best setting – as it gave me a little time to put the kettle on, light a ciggie and stick my head up in the pitch darkness and have a look for any vessel’s lights on the horizon. I knew which direction to look based on the radar screen, and sure enough about half way through my coffee a navigation light would appear, and it gave me a chance to work out if we were on a collision course. Strangely in the six times the alarm went off in the middle of the Atlantic, four of these were on a collision course. In all of them I simply called the ship or tanker on VHF channel 16, and let them know I was a single handing sailboat and they were more than happy to do a small course change to avoid a collision. This saved me having to harness up and change course and adjust the sails and reverse everything in the pitch dark after the ship had gone by. Which I had to do when the ships did not answer. There was an easy way to see if you are on a collision course with another vessel. You could plot the other vessels course on the radar screen and see if it intersected your course at the crucial time. Or the easy way and that was to wedge yourself in the cockpit and pick an object on the boat that is visually lined up with the other vessel – usually a stanchion, and do not move. If over a few minutes the other vessel has not moved to the left or the right in relation to the stanchion, but remains lined up with it as before, you are on a collision course! The longer time you give this the more accurate it becomes. Right up until you collide!

Also if there were any squalls on the approach you can turn up the gain on the radar and get an echo from the rainfall. Which meant that you could plot a course through the narrowest band of squalls and avoid the larger cells. To my surprise this worked out really well on many occasions. Before the radar was installed the approaching squall just looked like a solid wall of rain water coming towards you and it was pot luck on how long it was going to last. You would get the usual blast from the leading edge with the accompanying horizontal rain, and it would settle down slightly and go on for at least a half an hour. With the radar I often found that I could get through a small squall in around 10 minutes.

Trying out different sail combinations while under way. Getting the storm sail in place for a quick change if needed.

While underway well into my daily routine, I heard a call on the VHF Marine radio (local radio), from what sounded like ship on channel 16. I looked up and I could see the top of some vessel just coming up over the horizon, behind me. I answered the radio with my vessel name and VHF call sign VO9932. And the voice on the other end asked “What my intentions were?”. I had no idea what that meant, – “What were my intentions”, and all I could think of was – I was going to finish the repair I was working on, and after that I was thinking about having some lunch. But I do not think that was what he was asking. So I asked him to identify himself again and repeat his question.

It turned out to be the the U.S. Navy fleet, and they were coming up fast behind me. The correct reply he was after was, that I was a single-hander sailboat, and I was going to stay on the course that I was currently on. He said that they would adjust course (to avoid a collision with me), and asked if I was in need of any assistance? To which I replied “A tow to the Azores would be handy”. No reply … long pause …(no sense of humor), So I finally replied that “All is in hand, and I did not need any assistance thanks”, and wished them “Bon Voyage, this is the sailing vessel Toucan VO9932, standing by on channel 16”. And watched an aircraft carrier and a couple of battle ships and various support vessels, pass by. It was fascinating right up until I just happen to glance at my GPS to record the location of the radio connection, and to my horror the GPS no longer worked. All it said was there was no signal. And this hand-held GPS was the only one I had. It was mounted on the cockpit main bulkhead and was powered by the ships batteries, and I never turned it off – for any reason. Merd! I quickly checked the power connection and it was fine, and checked the little built in antenna, and it also was fine. But it refused to pickup any satellite signals. Merd again! I was starting to think what could I do. I had a sextant on-board and all the reduction tables, and I had my sailors ticket in celestial navigation. I guess I could navigate by dead reconning (compass, speed and time) and adjust for any currents, with daily noon updates from taking a position from the sextant which would give me a line of position across the chart, and I could advance the one LOP by the distance and direction traveled over the next days noon LOP and that would give me a fairly accurate position – well fairly accurate for being in the middle of the Atlantic. But it would test all my skills to navigate to some tiny islands – the Azores, 1,000 miles off of Africa. The old joke went through my head, that the worst would be if I miss them and arrive at land and if every one is black, turn left and go North until they are white again. No panic after all sailors have been navigating by sextant for hundreds of years. By then I noticed that the US fleet had gone over the horizon and was out of sight, and I looked at the GPS and it was working fine again. It was the fleet that had jammed the GPS signal around their vessels. Bastards, they could have said something, instead of having me in a panic. Ok I know what you are thinking – it is their satellites that we all use. Fair enough.

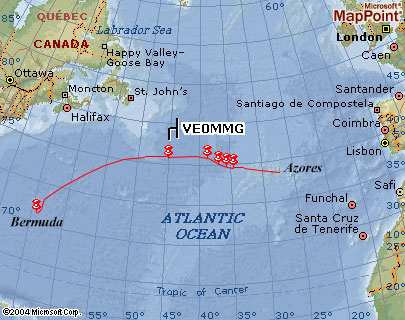

An arc towards the Azores

Transiting an arc between Bermuda and the Azores (riding the Gulf Stream). The email messages with lat. and long. got a pin.

When ever I put in the latitude and longitude into the email message the data went along with the email and when Deb retrieved the email she could also see my position (indicated by a pin) on a small chart. The first part of the trip went fairly quickly as I was riding the currents of the Gulf Stream as well as sailing along on top of the moving water. One strange phenomena was in the middle of a clear sky was a line of narrow round clouds sort of like a dark tube stretching from the horizon to the horizon from a North West to South East direction. When I sailed under the cloud tube the winds suddenly picked up and came from a different direction. I imagine that this was a cold front, and it reminded me of the lines you get on a weather fax chart indicating a cold front, I half expected the cloud tube to have the little pointed triangles running along the length of the front. Weird!

While sailing along I noticed that the stitching in the sacrificial Sunbrella sun guard that was put on the Genoa sail (roller furling strip) was starting to deteriorate and the sun guard was starting to flap. So with the weather being good and the seas relatively calm, I rigged a double harness attached to the deck and down from the mast that allowed me to lean with tension over the lifelines I started to hand stitch (with a leather palm and curved sail needle) the sail while it was still up, and maintain speed while underway. It took quite a while but I was able to restitch all along the bottom and as far up the sail as I could reach. This seemed to do the trick, as I thought that this was the part of the sail that got the most wear and tear rubbing against the life lines and the stays every time I tacked the Genoa over in the last 10 years.

The sails rigged and bagged for a quick deployment. A small Jibb forward and the storm sail on it’s own track on the mast. (note the 6 man life raft strapped down on the deck).

Things went really well for the next couple of weeks, and the routine I established kept me busy all day and night. As I approached the Azores, Deb told me that she had booked me on a flight out of Horta, Ilha Do Faial, to Lisbon, Portugal, and another to London, England and on to Edinburgh, Scotland. Starting that Saturday at 7:30 pm. I had my work cut out in order to arrive in time for the flight. By my calculations I would arrive in Horta on Saturday morning around 5:00 am. So in order for me to find and book a slip in the marina and shut the boat down, clear Customs and Immigration and pack for a trip back to Scotland I thought I had better start packing and preparing the boat as I was arriving. We were to join our Canadian relatives – Heather, Terry and Jenn in a 3 week drive around the Whisky Trail in Scotland (another good story). Visiting all the distilleries. A trip not to be missed.

I finally could see the peak of the volcanic mountain of Ilha Do Pico, what seemed like to be floating in the sky on it’s own, and nothing below it – strange. As I slowly got closer, It slowly grew further and further down towards the sea – Land Ho! I shouted with joy. I had been dying to do that for ages. I was so pleased to have crossed the Atlantic by myself and had a perfect trip. A huge sense of accomplishment. So now it was action stations, I started tossing overboard (while well out to sea) all the root vegetables that I had remaining on the boat as well as all the eggs and fruit and anything that was perishable and would not last another 3 weeks that I would be gone. I quickly packed a bag for the trip, with every thing I would need. Installed all the fenders and dock lines as I approached the marina. Only to see the marina chock a block – full. It was their regatta week that they hold once a year and boats from all over were crammed into the marina! Even the Customs and Immigration dock was 3 boats deep on the dock. So there was nothing else for it, but to tie up on the 3rd boat out. I pulled up alongside and knocked on the boat, and a sleepy sailor emerged and listened to my plea of just arriving from Bermuda and having to clear practique. And said “Sure just tie up”. So with passport and clearance and boat papers in hand I scrambled over the 3 boats to the dock as quietly as I could. I was dying to tell someone that I had just sailed the Atlantic by myself, and as I went into the customs office, there was a crowd of sailors all waiting in a long line. So after a few minutes the captain in front of me asked – “So how long did it take you to cross the pond?” What a downer. Everybody in this line had just done the same thing! Mind you I felt a little better when I heard that some of the crews had taken 26 days or such to do the passage, and this was on much larger boats than I had, and with full crew of six sailors. So I was pleased as punch to state that today was the 19th day since leaving Bermuda – single handing on a 32 foot sailboat – yes, get it up ya!!!

I managed to move the boat and tie up to a single large Canadian boat that was on the concrete dock, and arranged the marina to tow Toucan to a slip (berth) once the regatta was over. I finished packing, and shut everything down and closed all the sea cocks, and disconnect the batteries at the main switches, and put everything of value down below, as well as leaving out a few extra dock tow lines (in nautical fashion) in the deck. I still had one problem, I did not have any money in the local currency, something called – Euros. I had American Dollars, Scottish pounds, Eastern Caribbean dollars, and Trinidad and Tobago dollars, but no Euros. And the taxi drivers would not take anything else. The Canadians that I was tied up to came to the rescue, and swapped a twenty US $ bill for 20 Euros, enough to get me to the airport and have a cup of coffee. And before I realised it, my great adventure was on hold.

When I got to the Airport I managed to call Deb collect and told her that I was in the airport and had an hour before the plane was due to leave, and asked her the pin number for my credit card. I never use it so I had no idea what the number was. Half an hour later I called her back (collect again) and had the number in hand. Off to the teller machine and moments later I had cash in hand! So where was the cafeteria? I had not eaten anything in 2 days. Found it – no food left, as they were about to close. There was vending machines, but I did not have any coins. And I saw the cafeteria closing the shutters, and I could not ask them for some change as I did not speak any Portuguese. By the time the plane had taken off and offered the passengers a sandwich I was ravenous. But a crappy sandwich never tasted so good. Ah bread, and even ice in your drink! At the Lisbon International Airport they had a Burger King – I pigged out!!!

Leg 3 Azores to Falmouth, England (1,327 miles)

Toucan in a berth in Horta, Azores.

Arriving back in the Azores, the airline managed to loose my luggage – what little there was. And while I was away I had a call from the marina, to let me know that another boat had run into the side of Toucan. The damage was not too bad upon examination, a broken sanction and some twisted stainless steel life line. But the bolts that held the stanchion on through the deck had sheered off and would have to be repaired from the inside. Many years ago i added horizontal lockers to the inside of the boat, and these would have to be removed first before I could get access to the under deck. The offending boat agreed to pay for any repairs, so it was just another job to do.

While working on the deck a tall sailor was walking down the dock and said hello, and in our following conversation he said that he remembered seeing Toucan on the dock in Bermuda. He said his name was Lukasz, and he was crew on one of the 2 Polish racing boats that were behind toucan in St.Georges. In fact he turned out to be the guy that was was up the mast working on the rigging most of the time we were in Bermuda. Lukasz was in a bit of a dilemma. Apparently the owner of the boats had agreed with Lucas that he would pay for his passage to St. Martin where the boats were located, and pay for food and expenses if Lukasz – a licensed captain and his friend Jacob would sail one of the boats back from St. Martin, in the Caribbean, to Poland. Now that Lukasz and Jacob had arrived in the Azores, the owner of the boats had just informed Lukasz that the situation had changed. He was no longer willing to pay to have the boats sailed the rest of the way to Poland and that Lukasz and Jacob, would now have to pay him for the privilege of sailing one of his boats back home. Lucas was not in a position to do this and had booked a flight to fly home. He was really disappointed as it would mean that his transatlantic voyage was cut short, and he would not be able to complete it. I told him that the law was on his side and that in a conflict of this kind that the owner of the boat was legally responsible to fly Lukasz back to the nearest port that he originally left from. All Lukasz had to do was report the situation that the owner changed the agreement of the delivery of the vessel to the Customs and Immigration and they would take it from there. All they would do is add the cost of a flight to any monies owed at the marina and not release the boat until all the monies owed were paid in full. I offered a chance for Lukasz to finish his transatlantic crossing on-board Toucan if he wanted. I would be glad of the company especially a seasoned captain. So we went to the Customs and Immigration and told them of the situation and that Lukasz wanted to sign off the vessel that he was currently on, and officially sign on to Toucan as crew. Job done!

Lukasz in Peter’s Sport Bar, Horta, Azores. Our original Canadian Flag hanging from the ceiling.

I spent the next week working on repairing the broken stanchion, and Lukasz insisted on giving me a hand, to which I was grateful. It was a pretty straight forward repair. Remove all the cabinets and gain access to the under deck and remove the broken bolts. I had a spare stanchion on board and we reinforced and sealed the area, and put in new bolts, and put all the cabinets back in place. I also had the sacrificial roller furling strip totally re-sewn onto the Genoa sail where the stitching had disintegrated. And we spent a few days walking to the supermarket and carrying back the groceries that we would need for the next leg of the trip. As well as a few nights at the famous Peter’s Cafe Sport Bar – there was not much else to do in Horta once it got dark!

We came across an old salt, James, who was in his mid 70’s who was also preparing to set sail for England. He had an old wooden boat and brown canvas sails, and would not have looked out of place sailing in the 1930s. The only electronic equipment he had on his boat was a hand held radio, with a small solar panel to charge it up once in a while (no engine). All his navigation lights were kerosene with reflectors. Apparently he was single handing back to Blighty to get married! We were on our way to Peter’s Sports bar to get the latest weather fax, as we found in all marinas that there was always too much radio interference to receive it ourselves. We made sure we dropped a copy off to James, and wish him the best of British. Since the weather forecast looked fairly good and since it was starting to get late in the season, we figured that we had better get a move on. The last thing to do was check out at Customs and Immigration and get our clearance papers, and go to the fuel dock and fill up with as much fresh water and diesel fuel that we could carry and push the front of the boat away from the dock and jump on and we were underway again.

Underway

The first few days went very smoothly and we settled into a routine quite well and shared a watch round the clock. With some overlapping watch times for meals proved a good time to get to know each other. Lukasz was very amiable and easy to talk to, and swap sailing stories (tall yarns). This was vital as it is really important that the crew get on well together. When things get hairy, which they can do, it is good to know you have each others back, and can rely on each other. A couple of days out and we ran into the Azores high and both the winds and seas dropped to nothing. At this time Lukasz spotted something in the water and it turned out to be a whole group of leatherback turtles. We had seen these very large turtles laying eggs on the beach while in Trinidad – the largest of the species, about 4 foot wide and about a 5 foot long at the shell. We tried to get this on video, since we were not doing much else. The batteries on the video camera were no longer holding a charge so I had to turn on the 110 volt system on the boat and plug in the charger / power supply in to the camera and connect it with a long extension cord just to get the camera working. Just their

heads were visible above the water, and they were all surfacing all around us. But every time we slowly motored the short distance over to one they would dive and that is the last we could see of them (see the video).

Lukasz giving the roti a “lick with the flame”.

It was a bit of a fun distraction while we had no wind. While traveling long distance, I was for sailing only and not motor-sailing, thus retaining as much of the diesel fuel as possible in case we needed it later on for arriving at a port, or some other emergency situation. However we would still run the engine for an hour each day to top the batteries up, and to keep the engine well oiled internally. While becalmed it was an opportunity to check all the systems and double check the lashings to make sure every thing was secure. Easier to do this while it was quiet and still, than having to secure something major when it is bouncing and jumping around. Lukasz took advantage of this to bake some flat bread. I had a couple of pounds of Roti flour from Trinidad, and we followed the recipe on the package. They did not look like the Roties that they sold in the market. They were fried in a frying pan and looked rather floppy and un-appetising. I remembered Kathleen – security at TTYA mentioning that they “need a lick with a flame to finish them off” so we held them in the cooker flame for a few moments, and they puffed right up and singed and looked great! Thanks Kathleen! The galley looked like a flour bomb had gone off and a large clean up job was in the cards, so Lukasz cooked up the rest of the Roti flour, so we would only have to clean up once. We had dozens of freshly made Roti bread to eat.

Later that day I could see some familiar brown sails on the horizon, and it was our recent acquaintance – the old salt from the marina. I called him on the radio as we had just finished getting a weather report from Herb in Mississauga and there was a cold front heading our way for the next day or two. And I wanted to pass on the information to James so that he had plenty of time to batten everything down and prepare a meal or two in advance. After a short conversation, as his hand held radio battery was a bit low, we wished him good luck, and watched him very slowly go beyond our horizon. To this day i do not know if he ever made it to England safely in what we did not know it yet – was the bad weather to come.

As promised the winds picked up and the seas started to have a fair size swell to them, but Toucan was riding them quite well. I got a little video in after the second day, when it calmed down a bit. The wind generator was going great guns in the 30 knots of wind. It always made for a rough night, and when you tried to get a little shut eye, when you were off watch, your head was always rolling from side to side on the pillow. Making sleep a lot more difficult. Eventually you get so tired that even this will not keep you awake. Every one says that it is like trying to live inside a slow moving washing machine.

A 60 ft Fin Whale shadows us for 3 days and swims under the boat (see video).

After the cold front had passed and the seas had calmed down again. I went on the fore deck and checked that all the lashings were still in good order, and that every thing was secure. The only sound was the boat moving through the water, nice and quiet. Then suddenly I heard what sounded like air being released from a compressor hose from not too far a distance off the boat, which made me jump as I was not aware of any other boats in the area. When I turned I could see the last part of a whale in a dive. I shouted Whale!, Whale! to which Lukasz came bounding up in a flash from below, searching the back of the boat, thinking I had fallen overboard, and was shouting for help. I guess better to render help quickly and then translate what I was shouting.afterwards. I pointed to the general direction and again shouted “Whale!” We scanned the area, and sure enough a couple of hundred meters off the boat a 60 foot Fin whale did another rolling surface, and the sound that I heard was the whale “sounding” or exhaling and taking a breath. “Wow!”, we were both saying simultaneously. We both watched it do this time and time again for about half an hour as the whale eventually swam off. I was thinking now – why didn’t we get the video camera out. Or take a few pictures. We then slowly got on with the business of sailing again. The next morning the swell had picked up a little and the whale was back, this time with a calf, which made me think it must be a different whale. But they seemed to keep their distance, but you could still see them in the swells. The third day the big boy or another one was back and this time as he surfaced he was closer to the boat each time. I grabbed the video camera, and got the 110 volts up and running and with the extension cord and managed to film it. Lukasz was on the forward part of the deck saying “That’s beautiful!” as the whale approached even closer, and I was murmuring “Thats too close “, and the next surfacing, “Thats to F^%$&&^ close!” as the whale went under the front part of the boat and surfaced on the other side! I always say as far as boats are concerned, close is ok, but touching is not good! Especially if the whale is twice the length of the boat! I take it back, maybe all those survival stories of sailors having their boats sunk by whales and not semi-submersible containers was true. At least at that moment I was a believer.

Lukasz with a Jack fish, now where are the chips!

We managed to trail a fishing line of the stern (back of the boat) as we sailed along, in the chance we could supplement our diet, when it was not too rough out. But there was quite a few days when we did not have even a nibble, nor where there any sea birds present for quite a while as well. We were using the 300 Lb test line with a Cuban Reel, and a long section of steel leader with a six inch jointed fish lure with 3 sets of treble hooks. Which had proven to be quite good over the years. It was attached to the main winch in case we caught something too big to handle by hand hauling – we could always winch it in. I remember when we were trailing a line off the coast of Venezuela and went through a school of Whahoo fish, after we caught a large 30 pounder, Deb put the line back in and when we caught another. We were hauling it in and I thought it had gotten away. When I examined the lure there was a head of another large Wahoo that had taken the lure, but it was sheared just past the gills with such a clean cut that it looked like it had been done with a samurai sword. Thankfully whatever had bitten a large Whahoo had missed the lure, because I would have hated to have had to deal with that big bugger.

When we finally did catch a fish it was so big that the lure ripped out when I tried to haul it onboard at the very end. Lukasz had the short gaffing pole with a large hook but we were cramped for space off the stern quarter, and it was difficult to a land a good strike. We put the lure back in and in a short while had another fish on the end. This time we were well prepared to land it better, but this fish was only half the size of the other one – about a 15 pound Jack, and was no trouble in landing it.We immediately cleaned the fish and prepared a little egg and flour and seasoning, and had our selves a great fresh fish fry.

Hurricane Ivan (Wikipedia)

On September 8, Hurricane Ivan crossed Grenada into the eastern Caribbean Sea. It vacillated in intensity, ultimately reaching peak winds of 165 mph (270 km/h), which is a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson scale. That day, a tropical storm watch was issued for the southern Dominican Republic from Santo Domingo to the country’s border with Haiti. A hurricane watch also issued for the southern Haiti coastline, as well as for Jamaica. On September 9, a hurricane warning was issued for Jamaica and the Cayman Islands, a tropical storm warning was issued for western Haiti, and a hurricane watch was issued for southwestern Dominican Republic. Hurricane Ivan passed just south of Jamaica on September 11 and just south of the Cayman Islands on the next day. By September 11, all of western Cuba, including Isla de la Juventud, was under a hurricane warning, and Ivan passed just southwest of the western tip of Cuba on September 14.

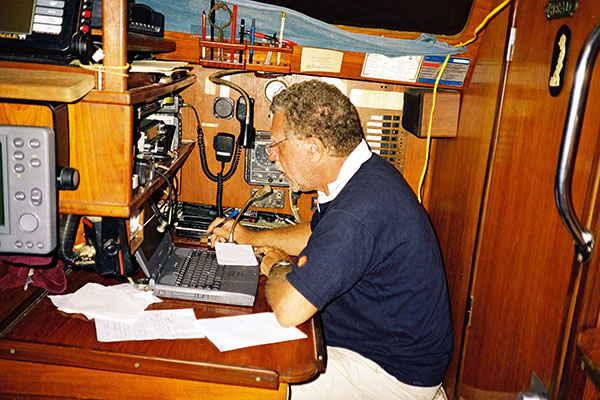

Willie on the radio with Herb (Southbound II) getting the latest weather report.

We had heard from Herb that a low pressure area was coming off of Europe around Spain, and moving slowly Westward, so we continued on our northerly route to try and avoid it. We were as far north as the southern end of Ireland, but still 500 miles to the East. When word was the low pressure started veering to the North West, so we changed our course to go South-South East, again trying to avoid it. This low was massive. As we progresses the weather steadily became worse. Becoming gale force for a few days. We had already reduced all the sails and had only the loose footed storm sail up, hard to the side. The wind generator was screaming all the time, so we had plenty of electricity. The wind and waves were coming from the stern port side and we were sliding down the large swells. We were too far away to hear Herb directly on the Ham radio, but were still able to get an email through to Florida, so this was how we communicated with Herb once again. The gales worsened into storm conditions, 55 knot winds and 25 foot seas so we carefully took the longest anchor rode that we had prepared earlier, and attached the 35 pound Bruce anchor to it with a large stainless steel (smooth) shackle, and dropped it of the stern. Both the ends were tied to either side of the boat to the dock cleats and the rode formed a very long v shape behind the boat with the Bruce anchor trailing at the far end. This was the closest thing we had to a sea anchor, and we hoped this would be enough to slow us down while sliding down the very large swells. We took down the Storm sail and ran with just the bare mast. There was not much else to be done. After observing the Auto Pilot for a while, and was amazed that it was handling these extreme conditions just fine. The radar was also working well under these conditions, so I was really impressed with the gear. Since the spray from the waves was now being blown horizontal there was nothing to be done other than battened down the hatches (closed the cockpit companion way), and wedged ourselves into our bunks to ride it out. We would still maintain a watch, but it was reduced to coming up every hour and do a visual check on the boat and conditions (and try and have a smoke). Reading a book while wedged in your bunk was a good way to take your mind of things, as the noise of what was going on all around was enough to put the frightners on you. It was a very rough night indeed, and at one point we must have slid down a particularly large swell as when we got to the bottom, we had such a large thump that it literally threw me out of the bunk. I checked the boat to make sure everything was okay, And it was still screaming out there but no worse than on the previous check.

After 3 days of this I was rather concerned with our progress. Were were still doing 5 knots under bare mast and with a sea anchor deployed, and were due West of, and heading for the Bay of Biscay. When ever a storm has this much energy, and the swells are this high, when you are in 26,000 ft. of water. When this enters a relatively shallow shelf like the Bay of Biscay, all that energy has to go somewhere and the waves will at least double in size. I did not think that we would be able to survive such conditions. I was not willing to find out! So we managed to get an email off to Herb and one to Deb asking for a complete rundown for any ports to the south, Spain or Portugal that we could enter in bad conditions. VHF port frequencies, Lat and Long, and so on. A couple of hours later when we checked the email Deb had sent all the information back, but there was also a weather report from Herb saying that there was only gales to the North. So Northbound it was. At 3 am in the pitch black, we very carefully hauled in the sea anchor, and got it securely stowed away, and raised the storm sail back up and changed course to the Nor Nor East for Old Blighty and the English Channel!

It finally started to settle down to just Gales to the North and we were now heading for the English Channel and Falmouth.

After a couple of days the conditions gradually got better. There was another sailboat that would occasionally pop up between the swells, and I noticed that they had a bit more canvas up than we did, and slowly passed us on the starboard side. But as the winds died down a bit we also took down the storm sail and raised the double reefed mainsail. and eventually a little roller furling genoa for balance. As we approached the English channel, we could see more and more shipping. The radar alarm was going off all the time, so we switched off the ring guard alarm and got back to maintaining a proper watch, for shipping. At one point there were 12 ships within the visible horizon going every which direction. Something we were having to get used to. The English Channel is a busy place!

There are a few shipping lanes in the English channel, well marked on the charts. I figured it was best to cross these as quickly as possible, and at right angles to the lanes. The seas were still quite rough, but the closer we got to land the seas eased a little. Land Ho!, well at least I thought so. Lukasz didn’t think so, and we had a long debate as to weather it was land or haze. Either way I was anxious for this part of the trip to be over, as we were both black and blue from bouncing off the hard parts of the boat. A few days earlier we had run out of propane gas, and that meant that there was no hot meals anymore, and worse – no coffee.

In what seemed like an eternity of squally weather, we finally entered Falmouth Bay, and the water was a lot calmer. We headed for the marina areas – there were lots of them. And as is the custom in many places I called Customs on VHF channel 16. There was no answer. I wanted to avoid wasting time and get directions to the customs office, so we could proceed there directly. We were flying the little Q flag – Quarentine. But after half an hour of calling, and not getting a reply, I finally gave up. By this time we were adjacent to one of the large marinas, and I said to Lukasz, let’s just find a slip and worry about Customs later. We motored into the marina and found a place to dock along side one of the floating pontoon walkways. We were exhausted. It took us 20 days to sail from the Azores to Falmouth instead of the estimated 10. And in some of the roughest waters that I had ever sailed in. But we were tied up, at Falmouth safe and sound. I was lucky to have Lukasz along for the trip, as it would have been a lot harder in those conditions without him.

We had a quick chat with some of the sailors in the sailboats around us, before hitting our bunks for a good sleep, and boy did we sleep! When we finally surfaced there was a thermos of hot coffee, and an invite to a hot meal awaiting us in the companionway. That was a nice gesture from the sailboat across from us. I guess we looked pretty bad when we arrived. I got off to the marina office and arranged for us to stay for a week. Then made tracks for the Customs house that turned out to be in the middle of the town. When I finally arrived there was 2 massive wooden doors that were locked, and I had to bang quite loudly until someone finally opened the door. I explained that we had just arrived from the Azores and would like to clear practique (check in to the country). The Customs Officer surprised me by saying that “They don’t do that here any more” What? This is a major port of entry and they do not require you to clear Customs and Immigration? He said that If I wanted to do that I would have to go to the airport, as they do it there. Or I could phone them if I wanted. I could not believe it. In the Caribbean, even the smallest island made you report to Customs and Immigration, and the ex-British islands made you fill out all the forms in triplicate. Some of these offices were no more than a shack on a sandy floor with an old school desk and 2 chairs, Hilsbourgh, on Carriacou for example. Where they also made you report to the police station, and the Harbour Master, and they didn’t even have a harbour! All they had was a long bay where you could drop an anchor. And now we find out that there is no real control over the comings and goings of small vessels in the UK. We could have been people or contraband smugglers, and just walked right in! It boggles the mind. When I got back to the boat Lukasz asked how it went, I had to tell him “It didn’t.” So to do things right, I called the Customs and Immigration at the airport from my mobile phone. I told them that we had just arrived from the Azores and he asked my name and the name of the vessel, and how many crew on board, and what were the nationalities. I said 2, one UK citizen, and one Polish citizen. He then asked if I had anything to declare, to which I thought for a moment. Normally I would declare how many bottles of rum, and cigarettes, and that I had a flare pistol (the Olin) and so on, on board. But I thought what was the point, as he was not interested in coming down to the marina anyway. and just delared “No, nothing to declare.” After I hung up Lukasz was asking “Didn’t they even ask for my name?” I replied “No, I don’t think they cared.” Strange. Welcome to the United Kingdom.

Leg 4 Falmouth, England to Edinburgh, Scotland (1,200 miles)

I planned for as short a passage as possible, as it was getting late in the season, and I wanted to get to Edinburgh before October 1st and avoid any more winter storms. I figured that it would take Lukasz and I about 3 days to sail the South coast from Falmouth to Dover, and about 4 days to sail up the East coast to Edinburgh. Since the prevailing winds are from the North West to the South West, I figured this way we would have an offshore breeze if we sailed up the East coast. So after a few days rest, we started to provision the boat for the week long sail. Now that we were in the UK we had to get different fittings and a different propane bottle for cooking. After refuelling and filling the water containers, we were off on the last leg of the journey.

I wanted to sail in a straight course line from headland to headland along the bays on the South coast and maintain at minimum distance of at least 3 miles off shore. This has always worked for us in the past when cruising a coastline and sailing the minimum distance and keeping well away from any dangers (submerged, floating pot markers, shipping or boat boys). Of course this is not always possible if you are sailing and having to tack back and forth, but it is a good course line reference to keep to. The sailing was going rather well, and we were staying out of the main shipping lanes, which were very busy. By the latter part of the second day we could see the White Clifs of Dover, and when on a tack that brought us closer to the shore, we could see Beachey Head Lighthouse against the white cliffs. I got out the video camera to capture this iconic image as we sailed past. The next hurdle was to get past the entrance to the Port of Dover. It looked like we were going to pass the entrance just before dusk on the third day. Sure enough, it was slow going as we approached the entrance. And talk about a busy port. The port has a large number of ferries coming and going from Dover to Calais in France, And it seemed that they were all departing or arriving just as we turned the corner at the entrance. It was like trying to push a pram across a busy 6 lane highway. And before we were finished it got dark. There was not much wind, so we were motoring at top speed – 6 knots, and had the mainsail up for stability. It was still pretty hairy avoiding the ferries. Finally we had the Port of Dover well behind us and made a course change for the entrance to the Themes Estuary. All night it was busy with ship traffic. In all directions, and it meant we had to keep a constant watch and check for any ships that were on a collision course. The Themes Estuary is another very busy area for shipping, and I was glad to see the back of that area. Another navigation hazard that we had not encountered before, was hundreds of giant wind generators in a large group, well out to sea. Fortunately our course took us further out past the wind turbines.

The seas were fairly calm in the lee of England, and with 15 knots of wind we were making great progress going north. One interesting section, Lukasz had just finished his watch and I took over so that he could get his head down for some well earned shut eye. I brought us as close to shore as I was comfortable with in the dark night. and did a tack back out to sea. The tide had changed and instead of having the current going with us there was a now a strong 4 knot current on against us. The currents flowed North and South, depending on the state of the tide. This coupled with the fact that the wind was also coming from the north and we had to tack the boat against it, meant that instead of making progress (course over ground), we had indeed lost distance to the North over the ground, and despite a hard sail tacking close to the wind as possible, the tide (current) has us actually going to the South. This shows up quite well on the tracking on the GPS, and when Lukasz surfaced from his sleep, noticed that we were further South than when he went to his bunk. He accused me of being a lousy sailor by actually sailing backwards during my watch. We had a good laugh, as we both knew that there was nothing that could be done when sailing against wind and tide. The real skill is to loose as little course over ground as possible. Of course now that he had taken his turn at watch again, and with the tide about to turn to the north, he was going to get to show off with the current adding 4 knots to our boat speed – the course over ground, and really fly along at 9 knots. I would never live it down.

Our final destination was now in sight – The Firth of Forth bridges. 5960 nm

We enjoyed one of the most glorious sunsets when we were about half way up the East coast. The entire Western sky was ablaze with reds and yellows. And one could not take some time to admire the wonders of nature in all it’s glory. The coast was always on the port side, and I’m sure we were passing some fascinating locations that would have taken many seasons to explore properly. One of the nicest bird and seal colonies we passed in the night was the Farn Islands. We have visited them several times since. They have 20,000 Puffin pairs, Mallards, Eiders, Commerants, Shags, Terns, Oystercatchers … and a few sheltered areas to anchor. I would have loved to spend a week or so there. Right next to it there is Lindas Farn, and Holy Island. A 12th century monastery, with a nice bay with lots of small fishing and sailboats, and both are very popular tourists destinations. To have our boat on anchor in the Farn Islands, would be a joy. But we were on a mission to get to Port Edgar marina before any bad weather was upon us.